According to the A.S.I. 15th Contest of the Best Sommelier of the World

What is Needed in Sommeliers

2016.06.09

text and photographs by Tadayuki Yanagi

As the culinary world spreads globally, the work of sommeliers is also going through changes. The diversification of wine and growing demand for drinks as a whole beside wine have made a wide-ranging knowledge and the ability to make proposals needed. Thought to what is needed in sommeliers will be given through coverage of the contest held over four days in Mendoza, Argentina starting on April 16.

The photograph at the top shows the tense final scene of decanting a magnum bottle. Sommeliers must comment in foreign languages and carry out service while under the penetrating stares of jurors, playing the parts of customers. Sommeliers must also be on the lookout for traps, which may be planted anywhere.

The participants from Japan were Hiroshi Ishida (left) and Satoru Mori (right). Although they both put up a good fight, they were eliminated in the semi-finals. Hiroshi Ishida finished 13th, while Satoru Mori finished 8th in the world. After this, Hiroshi Ishida will educate younger generations, while Satoru Mori will aim for the next contest.

A difficulty described as “that of the Olympic decathlon”

Is it a superior tasting ability that is needed in sommeliers? Or is it wonderful service skills? Or maybe an in-depth knowledge comparable to that of a zymologist? The answer is all of the above. The 15th A.S.I. Contest of the Best Sommelier of the World was held in Mendoza, Argentina at the foot of the Andes. The judging criteria are wide-ranging, with a difficulty heard from the audience as being “that of the Olympic decathlon.” The winner was the 31-year-old up-and-coming representative of Sweden, Jon Arvid Rosengren.

Benoît Gouez, Chef de Cave at “Moët & Chandon,” an official sponsor supporting the contest since the 6th contest was held in 1989, presents winner Jon Arvid Rosengren with the Moët & Chandon Silver Trophy featuring the engraved names of past winners.

Sixty sommeliers from 57 countries around the world participated in the contest. From Japan, it was Satoru Mori (representative of Japan) and Hiroshi Ishida (representative of Asia and Oceania) who took on the challenge. This was Satoru Mori’s third consecutive appearance, and Hiroshi Ishida’s third try after a 16-year break following the 2000 Canada contest. Although both moved on to the 15-candidate semi-final, their struggle ended there. They stepped down, unable to move on to the 3-candidate public final that would unfold. Of the female sommeliers participating in the contest, four moved on to the semi-finals, including Paz Levinson of host nation Argentina. Julie Dupouy, representative of Ireland, advanced to the finals and took third place. The female sommeliers’ high levels left a strong impression on the contest. Another candidate that remained in the finals was French veteran David Biraud. He was expected to win this time but finished second, one place higher than his performance in the contest before last held in Chile.

Up until now, full comments on aromas and flavors were needed from blind tasting, but this time the contest was focused on the specification of wine. Sharp senses are required to guess the varieties and regions based on aromas and flavors.

The criteria for the contest has become more sophisticated with each passing contest. Wine-producing regions have expanded around the globe, and contestants must now remember even regions in countries such as China and the Netherlands. A sommelier originally does not deal only with wine, but all drinks. In the final, there was even a challenge of selecting a Grand Cru coffee to pair with a dark chocolate.

Traps in the practical service skills area now go without saying. In the final, a trap was set in the challenge to improvise and assemble a meal to pair with the wine brought by a customer. The wine included a 45-year-old Domaine Ponsot Clos Saint Denis vintage, a fake wine that does not exist. Realizing this in itself is amazing, but explaining that it is fake without offending the customer is likely even more difficult. At the same time, there has been a tendency at recent contests for service to become careless due to thoughts focused on time restraints, however, ample time was given this time, and many candidates did not know what to do with it. No doubt the candidates were all the more paranoid that a trap might be waiting somewhere.

Third place winner Julie Dupouy in a challenge where an “Extra Brut” not found in Moët & Chandon is ordered. A thorough review of the sponsor’s products is necessary. And the explanation to the customer is evaluated for language ability.

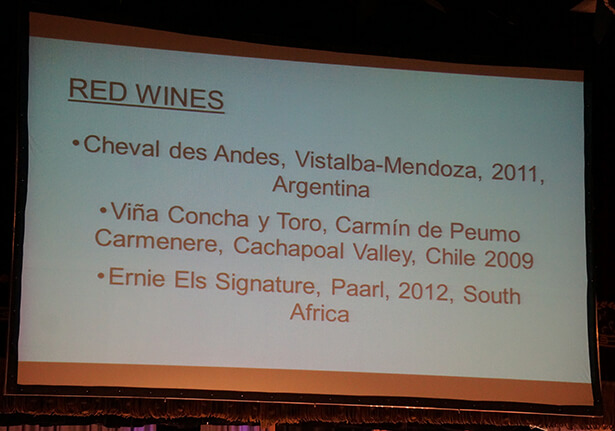

In the final, a blind tasting is done of four red and four white wines. Full comments are required for one variety, and the remaining three must only be specified. With the quality of the candidates remaining in the final, it is unlikely they will make mistakes in comments expressing aromas and flavors, methods of service, and food pairings, making it difficult to assign points. That being the case, this is likely why they must guess the variety, region, and vintage of wines.

Posing questions concerning managing and marketing is also a feature of this contest. In the final, the challenge “Persuade a customer that is hesitant to purchase this wine” appeared. Selling wine is also an important job for a sommelier.

In the final, many challenges take the form of quizzes. This is one for spotting mistakes on a wine list. Other challenges included writing the names of people, wineries, and pests appearing on the screen on paper. Sommeliers need to be filled with curiosity and the desire to deepen their own knowledge.

Required are native-like language skills and the ability to respond.

Looking back on the contest, first it is language skills that are important to become the best sommelier in the world. That does not mean simply being able to speak. One cannot win without being able to speak on a native level. Winner Jon Arvid Rosengren and third place Julie Dupouy both work in foreign countries. In addition, the sharp concentration to sense and react to small changes at the table, as well as the ability to react and take action at once are both necessary. Now that the range of challenges has expanded, it is necessary to hungrily expand one’s knowledge and to have the ability to memorize that knowledge. It is troubling that recently the number of sommeliers that do not read journals is on the rise.

Of course, winning the contest is not all there is for sommeliers. However, the challenges from the contest are all elements that are required in day-to-day service, and the exceedingly high-level subjects incorporated are also facts of their work.

David Biraud, who finished second, building on his success six years ago in Chile. This is from the examination for pouring the Moët & Chandon Rosé Impérial magnum into 15 glasses. It begs the question of just what kind of service he provides normally?

Current contest trends -General comments from Shinya Tasaki-

■A knowledge of all drinks and ability to propose them is questioned.

・ Local alcoholic drinks from various countries “besides” wine (sake, whisky, craft beer, etc.).

・ Nonalcoholic drinks based on the global trend away from alcohol (water, coffee)

・ Proposals for food pairings; purchasing advice

■High-level communication abilities were required.

・ The ability to gather knowledge, memory, and language skills.

■The rise of newcomers

・ Women coming to the forefront. Third, fourth, and fifth place were women.

Will a woman place first in the near future?

・ The rise of Northern Europe.

(Similar to Japan, improved wine educational institutions are the reason)