Japan [Aomori] Tasting Tsugaru

Where tradition and innovation coincide

2017.08.02

From October to May, onsen moyashi bean sprouts are a fixture on menus at local eateries such as Hikage Shokudo, a classic Japanese diner with a history of more than 120 years. The sprouts are the star ingredient in the restaurant’s specialty, moyashi ramen.

The roads that wind through the lush landscape of the Tsugaru Plain in Aomori Prefecture are lined with rice paddies and orderly groves of fruit trees. Once a sparsely inhabited marshland, the region was transformed into an agricultural center by land reclamation projects during the Tokugawa Period (1603 - 1868). Bounded to the north by the volcanic peaks of the Hakkoda mountains, the densely forested Shirakami mountain range to the south, and the Sea of Japan to the west, Tsugaru was notoriously inaccessible in ancient times, and the combination of the area’s secluded geography and heavy snowfall gave rise to a unique culture rich in culinary traditions. Today, a current of innovation runs through the region, building on its heritage and adding diversity to the food culture.

Viewed from above, the tiny village of Owani, which lies south of Hirosaki City, resembles an alpine hamlet in Central Europe, with clusters of colorful rooftops surrounded by sylvan mountain slopes. The covered footbath outside of the train station, where visitors can dip their toes in the warm water, points to Owani’s history as an onsen (hot spring) resort. The town’s geothermal spring, however, provides more than mineral-rich water for bathing: the heat it generates is also used to farm Owani onsen moyashi, an heirloom variety of bean sprout prized for its extraordinary, crisp texture.

In the past, the people of Owani relied on bean sprouts as a valuable source of protein and nutrients during the harsh winter months. At the Yagihashi Moyashi farm, Jun Yagihashi and Yuya Yagihashi use special techniques developed more than 350 years ago. The process starts with pouring 50 kg of golden kohachi-mame soybeans into a deep, rectangular pit. The beans are then sprinkled with a fine coating of soil the color of dark chocolate and then covered with bundles of straw sandwiched between hand-woven straw mats. A network of crisscrossed underground pipes funnels water from the hot springs beneath the seedbeds to warm the soil.

This labor-intensive method was kept a closely guarded secret for centuries. But as the number of producers has dwindled over the decades, the residents of Owani decided to create a program to train farmers and encourage young people like the Yagihashis to enter the industry in order to prevent the heirloom sprouts from disappearing.

Yuya Yagihashi began farming them as an off-season side project. “Once I started, I got really into it. It’s rewarding work,” he says, cradling a handful of onsen moyashi in one arm. With their long, slender shoots and yellow tops, the vegetables look like a bunch of white-stemmed flowers.

From October to May, onsen moyashi bean sprouts are a fixture on menus at local eateries such as Hikage Shokudo, a classic Japanese diner with a history of more than 120 years. The sprouts are the star ingredient in the restaurant’s specialty, moyashi ramen.

On the outskirts of town at Owani Shizen Mura, entrepreneur Hiroshi Miura and his son, Takashi, are using new technology to bring back an old idea: free-range pork farming. Owani Shizen Mura is a seven-hectare expanse of greenery. At the entrance, visitors are greeted by the farm’s pets ― a miniature pony, two sheep, a couple of goats, and a brood of fluffy chickens. The main area is the domain of several round-bellied pigs that roam the pasture, rooting for bugs and nuts and taking occasional dips in the mud pool.

“We do our best to create a stress-free environment. Removing stress on the animals leads to healthy development,” explains Takashi Miura, who oversees the farm. The pigs graze for 240 days -- 80 days longer than average ― to ensure that the meat is tender and marbled with sweet fat.

Owani Shizen Mura is an outstanding example of closed-loop agriculture. The farm supplements the pigs’ natural diets with additive-free animal feed made with leftovers collected from supermarkets and convenience stores. The food is sterilized and then treated with lactobacillus bacteria before being turned into dry feed.

The pig farm is an extension of founder Hiroshi Miura’s aim to combat food waste ― a serious problem in Japan. In 1998, Miura started Eco Net, a company that recycles discarded food to make fertilizer and animal feed. Nine years later, he launched Owani Shizen Mura.

“I had been thinking of how to create a local industry that would reduce waste and simultaneously turn it into a resource, and this is the result,” he says.

Miura has recently embarked on a new project to take his waste-not-want-not vision one step further. 2016 marked the opening of the Owani Shizen Mura Nama Hamu Juku, a repurposed elementary school building where Miura is now producing long-aged cured ham. The facility’s name ― which literally means, “cured ham cram school” ― is a reference to the building’s history, as well as a play on the Japanese word for maturation, juku. Rows of salted ham joints hang in the school’s old music room in front of a green chalkboard. Miura ages them for a minimum of two years, and the meat has a distinctive, deep flavor.

“I’m not trying to imitate Spanish or Italian ham,” he says. “I want to make something that people can only find here, in Owani.”

New developments are also afoot in the nearby city of Hirosaki, the apple-producing capital of Japan. Apples have been a major crop ever since the fruit was first brought to the region in the late 1800s. However, the number of producers has been declining as a result of the country’s aging population, coupled with the younger generation’s reluctance to take up agriculture. When hailstorms severely damaged apple crops in the Tsugaru region in 2008, orchardist Satoshi Takahashi realized that he needed to find ways to make the business more stable.

In 2014, he began making Kimori, Japan’s first artisanal hard cider, in a beautifully designed brew house in Hirosaki’s Apple Park. In addition to creating a new revenue stream for his farm, Takahashi says that his goal is to bring locals together and attract visitors to the region. He hopes that the Kimori project will prompt people to take a second look at the humble apple ― a staple that many now take for granted.

Apple farming in Japan ― where adverse weather conditions pose constant threats to crops ― is no easy task. But Takahashi finds great value in the endeavor: “Growing apples cultivates character and shapes you as a person.”

Kimori’s label, which depicts a single red apple on a tree, encapsulates his philosophy as a farmer. Every year after harvest, Takahashi leaves one apple as a gift for the birds.

“Nature doesn’t exist for humans alone. We have to share,” he observes.

While Tsugaru’s producers are looking to the future, the ladies’ cooking collective Tsugaru Akatsuki no Kai is making sure that the region doesn’t forget its culinary past. Led by Yoshiko Kudo, a keen-eyed grandmother with a kind face, the club gets together to share kitchen wisdom and prepare local specialties using traditional techniques for community gatherings or groups of visitors.

The focus is on intensely seasonal ingredients ― many of which are foraged or grown by the women themselves. The mizu (a plant in the nettle family) that goes into a tartare of the vegetable’s roots comes from the garden, while the slender bamboo shoots that are folded into steamed rice are gathered from the mountains.

“We try to use vegetables picked fresh in the morning and prepare dishes based on what’s available right now. In winter, when there are no fresh ingredients, we use preserved foods,” Kudo says. “Real food is made with what’s in season.”

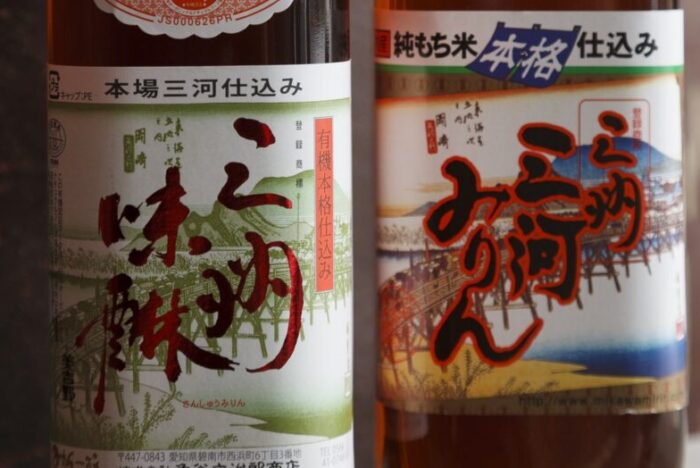

In the mountainous areas of Aomori ― where preserved foods were essential to surviving the long winters ― salted, dried and fermented ingredients form the base of the cuisine. The meals prepared by Akatsuki no Kai showcase an array of unique delicacies such as apples pickled in salt brine; tofu and vegetables simmered with dried cod; and hatahata-izushi, fermented Japanese sandfish. One of the region’s most iconic dishes, izushi is made by first salting the gutted fish, hanging them to dry, and then layering them with koji (an enzymatic catalyst made from rice and the mold Aspergillus Oryzae) to induce fermentation. The process takes roughly four months, and the finished product resonates with umami intensity.

In today’s busy world, such time-consuming practices are in danger of fading, but Akatsuki no Kai is working hard to pass the traditions and flavors of Tsugaru on to the next generation.

<Owani area>

◎ Yagihashi Moyashi

11-11 Owani Kawabe Owani-machi, Minami Tsugaru-gun, Aomori (Wanicome)

☎ 0172-49-1126

◎ Hikage Shokudo

55-2 Owani-aza Owani, Owani-machi, Minami Tsugaru-gun, Aomori

☎ 0172-48-3430

Open daily 11:00-19:00, irregular holidays

◎ Owani Shizenmura

420-200 Komakizawa Nagamine, Owani-machi, Minami Tsugaru-gun, Aomori

☎ 0172-47-6567

http://owani-s.com/

◎ Owani Shizenmura Namahamu Koubou

48-2 Koganezawa Hayaseno, Owani-machi, Minami-Tsugarugun, Aomori

http://namahamukoubou.owani-s.com/

<Hirosaki area>

◎ Hirosaki Kimori Cidre Koubou

52-3 Terasawa Tomita-aza, Shimizu, Hirosaki-shi, Aomori

http://kimori-cidre.com/

◎ Tsugaru Akatsuki-no Kai

44-13 Ishikawa Yagishi, Hirosaki-shi, Aomori

This coverage tour has been implemented under FY2017 “New Tohoku” Interaction Model Project led by Japan’s Reconstruction Agency.

”Gourmet Ride” event with the route to meet people and experience food introduced in this article Sep.30 and Oct.1, 2017.

Please learn more about the event.

http://or-waste.com/?p=22