Japan [Yamagata]

Mountains and the sea: Heart and soul of the Shonai Region in Yamagata

2017.09.28

Kenichi Ito’s day job is as a promotion specialist for the city of Tsuruoka’s gastronomy promotion division. But he has also been a practitioner of Shugendo for 15 years.

High on the slopes of Mount Haguro, in an area called Shonai Region in the northwest of Yamagata Prefecture, silence reverberates through the thick forest. The landscape pulsates with a wild vitality that can only be found in ancient places like this, where 500-year-old Japanese cedar trees line the path leading to the shrine at the mountain’s summit that symbolizes the rebirth of the spirit.

Along with Mount Gassan and Mount Yudono, Mount Haguro is one of the three sacred mountains of the ancient province of Dewa (in the present-day Shonai region) – known collectively as Dewa Sanzan. These three peaks are central to the mountain-worship religion of Shugendo, which blends Buddhist and Shinto beliefs with elements of animism. The site has served as the destination for religious pilgrimages for nearly 1,400 years and was once home to yamabushi, or mountain priests, who sought spiritual enlightenment through ascetic practices. Today, lay practitioners of the cult can be seen wandering through the woods wearing the traditional diadem and white-and-blue robes, a conch-shell trumpet in hand.

Kenichi Ito’s day job is as a promotion specialist for the city of Tsuruoka’s gastronomy promotion division. But he has also been a practitioner of Shugendo for 15 years.

I had traveled from Tokyo to the Shonai area to explore the fundamentals of the food culture, including Dewa Sanzan’s unique style of shojin-ryori – which translates as, “the food of devotion” – vegetarian cuisine eaten at Buddhist temples. Shoji- ryori is most commonly associated with Kyoto and frequently brings to mind images of tofu, vegetables, and tubers prepared to mimic the look and flavor of meat. In Yamagata, however, the cuisine is stripped of such pretensions; rather than masking the natural ingredients, preservation techniques such as salting and brining are used to bring out the essence of the foraged mushrooms and vegetables that form the basis of the local shojin-ryori tradition.

“The cuisine focuses on the bounty of the mountains,” says Shinkichi Ito, the chef at Mount Haguro’s sanrojo (priests’ retreat), a stately building with long corridors and tatami-mat rooms.

The meal consists of several small plates, offering a balance of textures and flavors. A dish of simmered bamboo shoots, deep-fried tofu, and shiitake mushroom is arranged to resemble the landscape of Dewa Sanzan. Creamy gomadofu (sesame tofu) -- freshly made every morning -- sits in a moat of sweet sauce thickened with arrowroot and spiked with ginger. Itadori (Japanese knotweed), a tart and crunchy wild plant reminiscent of rhubarb, is served with chilled tomatoes and sweet vinegar.

Ito tells me that all mountain foods have curative properties: itadori is a pain reliever, while miso helps reduce fevers. “In the mountains, there were no doctors. The yamabushi learned to use food to maintain health,” he says.

In the past, the wandering mountain priests also gathered seeds and cultivated heirloom vegetables. Thanks in part to these endeavors, Yamagata is still endowed with an abundance of traditional breeds, according to Yoshio Kobayashi, the chief editor of Cradle, a magazine devoted to the food of the Shonai region.

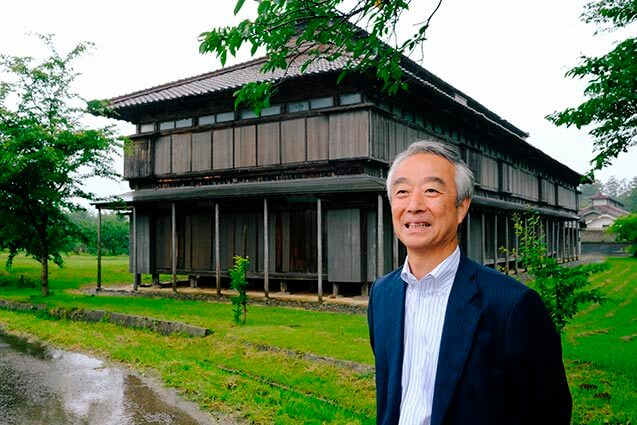

The Confucianist teachings at the Chidokan, which encouraged a love for study and self-improvement, have helped develop the Shonai region’s unique food culture, says Cradle editor-in-chief Yoshio Kobayashi.

[TSURUOKA TOPICS ~Tsuruoka’s shining light of gastronomical delights~]

Certified as the first UNESCO Creative Cities Network “City of Gastronomy” in Japan, 2014

In the middle of a wide-open field 20 minutes outside of Tsuruoka’s city center, Kiyoshi Yamazawa has taken on the mantle of Japan’s guardian of heirloom vegetables. Yamazawa, a sprightly 70-year-old sporting a diamond-studded earring in the shape of smiley face, is the director of Dainihon Denshoyasai Kenkyujo, a research facility and preservation center for heirloom plants. Inside a 1,000 square meter greenhouse, he grows more than 500 varieties of fruits and vegetables from around the country. Spiky, purple-tipped artichoke flowers tower over gargantuan cabbage heads that sprout from a plot in the center of the light-filled space. The air is fragrant with the aroma of nihon tachibana citrus trees, flowering cilantro, and chrysanthemum bushes. It’s like a scene from the Garden of Eden.

The secret to Yamazawa’s green thumb? Microbes, he says: “Microorganisms create the future of human beings. Chemicals have a history of hundreds of years, but microbes have been around for tens of thousands of years.”

His cultivation methods go beyond regular organic farming: all the crops are grown in soil that has not been exposed to pesticides or fertilizers for at least 20 years. After use, parcels of land are supplemented with fresh dirt and allowed to rest in order to re-establish healthy microorganism populations.

“The guy is a genius,” says chef Masayuki Okuda, owner of the Italian restaurant Alchecciano in Tsuruoka. “When he showed me 400-year-old tomatoes for the first time, I could finally understand the instructions in old cookbooks from the time of Escoffier.”

A culinary ambassador for the Shonai area, Okuda works with Yamazawa and other producers to support the revival of regional heirloom vegetables.

“We are trying to connect producers with chefs and consumers. The 2020 Tokyo Olympics will be a chance to introduce our produce to a global audience,” he explains.

[TSURUOKA TOPICS ~Tsuruoka’s shining light of gastronomical delights~]

Opening of FOODEVER TSURUOKA - A market for Tsuruoka’s gastronomical culture!

At Doyuuno, the recently opened restaurant beside Yamazawa’s farm, guests can taste 400-year-old cucumbers and tomatoes in their purest form – as a fresh vegetable extract. The clear juice is bright and grassy, with an earthiness that reminds me of a gazpacho-like liquid salad.

“I want to show people the flavor of history,” Yamazawa tells me. “If I can do this, anyone can.”

Agriculture is still the main industry in Yamagata, and it continues to be a big part of the local culture. Run by Mitsu Chonan, a soft-spoken chef with a philosophical bent, Chikeiken is a nouka minshuku, or farmer’s guesthouse, located in a quiet neighborhood surrounded by fruit orchards. Inside the lovely converted home that houses the restaurant, Chonan prepares traditional farmer’s fare using fresh and preserved local vegetables and seafood.

“We don't serve luxurious items,” Chonan says. “Cuisine is part of a social circle that supports the whole community. The wealthy shouldn’t be the only ones who can eat well.”

On the day of my visit, lunch is made up of of rustic dishes such as blanched okahijiki, a seaweed-like vegetable that grows wild in salt marshes; and a delectable stew of dried herrings and potato. Although the Shonai area extends to the Sea of Japan, Chonan explains, the mountains separating the shore from the interior meant that fresh fish was historically rare in the inland areas.

The food culture is completely different along the coast, where fishing permeates every facet of life. Tsuruoka’s Chido Museum is an open-air museum featuring the former residence of Tadaari Sakai, the feudal lord who established the Chidokan, a school that taught Japanese Confucianism and stressed the importance of developing one’s abilities. The museum also serves as a repository of artifacts documenting the importance of fishing in the region. Standing before a display case of bamboo fishing poles dating back to the 1800s, Tadahisa Sakai, the museum’s director, tells me that, in the days of the samurai, men were encouraged to fish at night to hone their powers of stealth and develop patience and concentration.

After leading me through an exhibition of antique fishing vessels and tools, we chat in the tranquil chashitsu (tearoom), which looks out onto the museum’s beautifully manicured garden. As we sip frothy matcha (green tea), we nibble on wagashi (Japanese sweets) shaped by hand using traditional wooden molds and silk handkerchiefs from the nearby Kimuraya confection company.

Later, I head to Sakamotoya, a traditional Japanese ryokan (inn) run by seafood master Ryo Ishizuka, who has laid out an extensive feast with more fish than any person could possibly eat.

Several varieties of seafood appear in a mind-boggling array of subtle preparations – each accompanied by a morsel of kitchen wisdom from Ishizuka. In addition to sashimi and salt-grilled nodoguro, there is a whole grilled flounder brushed with soy sauce, crispy tempura of fish tails, grilled sea bream basted with salt, trout covered in a thick and sugary sauce, and more. It’s the Iron Man of fish repasts. One of my fellow diners, a man from Canada, gives up before the dessert course. By the end of the meal, my other companion crumples on the tatami-mat floor in a food coma. As I survey the carnage of fish bones and empty plates, I feel a pang of guilt: I have left half of the flounder, but I’m too full to eat it.

“Most people can’t finish,” Ishizuka says, explaining that the lavish menu is a custom carried over from the olden days, when people took the leftovers home after elaborate banquets.

The next morning, Ishizuka treats me to an equally sumptuous – but mercifully less voluminous – spread for breakfast. For the final course, the chef has simmered my previous nights’ flounder in a sweet-and-savory soy-based sauce. The gesture of thoughtful thrift is touching: to waste such a pristine piece of seafood would be unforgivable. The fish is almost more delicious than it was the night before, and I savor every bite.

Column: Inoue Farm

The mineral-rich soil of the Shonai region has made it one of Japan’s leading rice-producing areas. At Inoue Farm, located in the middle of this fertile plain, father and son Kaoru and Takatoshi Inoue work side by side to grow rice with minimal fertilizer or pesticide use. Instead of agrichemicals, they spray their fields with a mixture of seaweed extract and sugar cane nectar.

In fact, the farmers in Yamagata’s Shonai area were among Japan’s earliest adopters of organic agriculture. “Perhaps it’s because the seasons here are so distinct,” muses Takatoshi Inoue. “When you’re working outside all year, you can really feel nature.”

[TSURUOKA TOPICS ~Tsuruoka’s shining light of gastronomical delights~]

If you are interested in traveling to Tohoku, learn more about our travel plans designed to facilitate the discovery of food culture in farming and fishing villages!!

https://r-tsushin.com/en/journal/japan/food_tourism_tohoku.html