Japan [Iwate]

Iwate's enduring food traditions

2017.08.15

Restaurant L’aureole stands atop a steep cliff overlooking the tree-dotted Sanriku Coast of Iwate Prefecture. On a drizzly morning in early July, waves lap against the rocks in the craggy inlet below. Over the horizon, a thick fog begins to creep over the water, muting the color palate of the seascape like a Turner painting.

“As the day goes on, you can watch the fog float overhead and then disappear,” says Katsuyasu Ito, L’aureole’s chef-patron and one of Iwate’s most prominent culinary figures. For the past 22 years, Ito has endeavored to promote the prefecture’s food culture.

The fog is created by the Yamase, a cold eastern wind that hits Iwate’s coastal areas during Japan’s summer rainy season. The inauspicious timing of the Yamase – compounded by heavy snowfall that buries mountain villages in the winter – made rice production difficult throughout much of the region’s long history. Widespread famines, which have been documented since the Edo period (1603 – 1868), were a constant threat. To cope with the challenging terrain, farmers cultivated less capricious staples such as wheat and buckwheat to supplement the wild zakkoku grains – millet, amaranth, and, and egoma (a relative of the perilla plant) – that grew in abundance.

The historical lack of rice led to the development of a strong noodle culture (Iwate is synonymous with buckwheat soba noodles and also boasts a range of other noodle specialties), and crafty locals devised ingenious ways to replace rice in recipes. At L’aureole, Ito shows me strands of dried potatoes hanging out on the veranda. They are white and slightly flattened, with chalky surfaces that give them the appearance of stones. Harvested in winter, the tubers are submerged for weeks in frigid river water, and then hung to dry for several months. The dehydrated roots are ground into a powder to make mochi ― chewy dumplings typically made from sticky rice flour and filled with sweet bean paste. A similar method is used to preserve potatoes in the high-altitude Andean villages of Peru, but I had never expected to find something like this in Japan.

Dried potatoes are the first of many surprising discoveries I encounter in Iwate. Even for long-time residents of Japan, the region offers a treasure trove of exotic ingredients and new gastronomic experiences. Iwate encompasses the second largest landmass on Japan’s main island, and the diversity of its flora and fauna is astounding. The mountains yield wild vegetables and herbs, along with a wealth of edible mushrooms such as matsutake (pine mushrooms), beloved for their woody aroma, and sakuratake, lavender-tinted mushrooms with wide, flat caps. The mix of warm and cold currents in the Sanriku bay provides ideal conditions for many species of fish, shellfish, and seaweed – a mainstay of the region’s cuisine. Iwate is famed for kombu (kelp) and wakame seaweed, but lesser known varieties such as funori – a purplish species of marine algae with a popping texture – and matsumo – a kind of seaweed with feathery blades reminiscent of pine needles – are eaten regularly, added to soups or eaten as salads.

At L’aureole, chef Katsuyasu Ito fuses French techniques with Japanese sensibilities in ways that bring the history and food culture of Iwate to the fore. He uses all local ingredients: seafood from Sanriku bay, game procured from hunters, and fruits and vegetables grown on nearby farms. Around three times a week, he forages for plants, mushrooms, or seaweed. A dish of grilled venison comes drizzled with a reduction of yamabudo wine ― made from a wild berry native to Iwate ― alongside a delicate crepe made with dehydrated potato flour. The result is a modern expression of regional flavors.

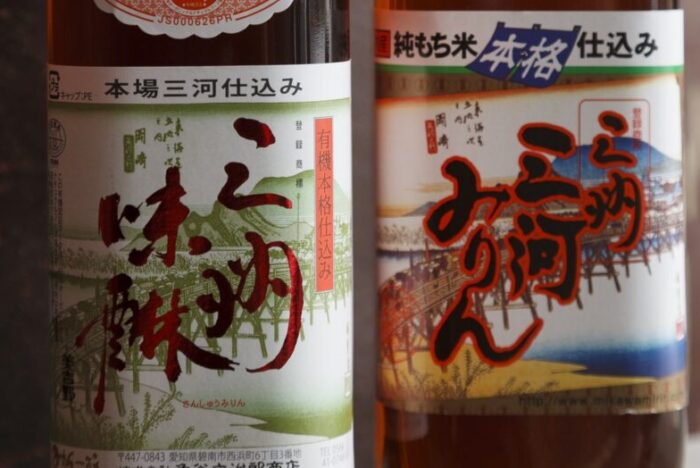

The traditional cuisine is based on fresh vegetables, often gathered from mountainside forests. The recipes have been passed down through the years by generations of the area’s women, who convene in cooking clubs to apprentice with masters of the craft. Kyoko Ichinokura is the undisputed doyenne of Iwate’s soul food, or kyodo-ryori. After moving to Iwate as a young bride, she learned the region’s food customs and gradually added innovations of her own. At 92, Ichinokura is still as sharp as a tack and continues to mentor scores of cooks. She is poised and immaculately coiffed, and when we meet she has me taste a sauce of freshly ground walnuts, miso, and a touch of mirin (sweet cooking liquor).

“The mirin prevents the walnut oil from going rancid,” she notes, dropping a tidbit of kitchen wisdom. Sweet, savory, and nutty, the sauce is used to dress a dish of blanched warabi (bracken fern), a long-stemmed wild vegetable that must be parboiled to neutralize toxins before eating.

Ichinokura’s preparations are meticulous, demanding both time and attention. The extra efforts preserve the flavor, texture, and colors of the natural ingredients. Food, she says, should always be beautiful; it must delight the senses. A classic assortment of vegetables simmered in dashi (broth), illustrates the point. All too often, cooks boil the ingredients together, blurring the flavors and staining all of the elements the same indeterminate shade of brown. Ichinokura prepares each item separately. Her dish resembles an edible landscape, with twists of vibrant green kombu, orange chunks of carrot, and the jade stems of fuki (butterbur) nestled against chubby bamboo shoots and round slices of spongy fu (gluten).

Ichinokura’s star pupil, Tomoko Oomori, who runs an inn in the city of Tono, is carrying on her mentor’s legacy and, at the same time, tweaking recipes to make traditional cuisine more compatible with the rhythms of modern life for home cooks.

Iwate’s producers understand the importance of connecting the past and the present. In Yahaba, a short drive away from Morioka city, the NGO Yahaba Yamabudo no Kai is working to preserve the region’s wild species of yamabudo berries, which are in danger of disappearing. Packed with vitamins and antioxidants, the fruit has played a significant role in maintaining the health and vitality of the local people since ancient times.

Farther south, in Tono, farmer Sachio Egawa launched a one-man campaign to bring back local doburoku, the sweet and slurry-like sake that was commonly brewed by rice farmers.

Although the practice of home brewing has been outlawed since the late 1800s, Egawa fought for the right to drink Iwate’s traditional liquor with the region’s traditional food – kyodo-ryori. His efforts led to changes in licensing laws and the establishment of the first special economic zone in Tono.

Since becoming the first person in Japan to win permission to micro-brew the drink, Egawa has created three varieties of doburoku to pair with the local specialties he serves at his pension, Milk Inn.

Toshihiko Nakamura, who owns the shellfish farm K.H. Base, pulls on a pair of lemon-yellow waders as he prepares to take us out on his boat in Yamada bay, an idyllic sweep of sea on Iwate’s central coast.

“We’ll sail out to orlanda-jima (Holland Island), just to take a look,” he says, pointing to a diminutive green islet floating in the distance. The spot was once a popular beach destination for day-trippers, but rising waters caused by the earthquake and tsunami disaster in 2011 have diminished the shore. Still, the area is beautiful, the crystal water a surreal shade of aquamarine.

A third-generation fisherman, Nakamura has been farming oysters and scallops for more than 20 years. When the tsunami hit, however, all of his shellfish rafts were washed away – along with his home. Fortunately, no one was harmed but his business was devastated.

“It was horrible, but we were encouraged by our local customers and fans around the country. I felt like I had to continue,” Nakamura recalls. Slowly, the company began to rebuild and is now thriving once again.

As the boat pulls up beside a wooden raft, Nakamura plunges his hands into the sea and reels in a line of scallops. The bivalves dangle from the rope like bracelet charms. In a flash, he pries open the shells and cuts the meat from the bright orange roe. The flavor is exquisite – a blast of sweetness, brine, and umami in equal measure.

The office of K.H. Base has moved into a new building up the road from the original location, and Nakamura tells me that he is building a brand new house for his family. “The construction is almost finished,” he says, unable to suppress a smile. The rain has lifted, and there is a gleam of contentment in his eyes as he scans the coastline.

Column: Koya Yauemon -Living history-

Hidden deep in the heart of the Iwate countryside, Koya Yauemon offers a tranquil retreat from the hectic pace of city life. Built more than 180 years ago, this stately Japanese minka (folk house) is lovingly maintained by owner Chihoko & Nobukazu Yamada.

Passing through the entrance feels like stepping back in time. With its compacted clay floor, the doma, or kitchen area, is cool and spacious. The living quarters are built on a raised platform, with a long corridor leading to the tatami-mat covered rooms in the back. Soft light filters in through the shoji paper screens, illuminating the dark wood interior.

The rooms are handsomely appointed with works of art and antiques. Yamada spent 40 years gathering those vintage items. A collection of large woven baskets sits on a high ledge beneath the magnificent vaulted ceiling; an art deco clock hangs above the door.

From May to November, the Yamadas open their home to visitors who share their appreciation for history and esthetics and want to experience staying in a traditional Japanese house.

“We live in a culture of convenience, rich in material things, where everything has become disposable,” Yamada reflects. “Through the Koya project, we want to convey the pleasures of simple living.”

Data

Coastal Areas:

◎ Restaurant L’aureole (Tanohata-mura)

309-5 Akido Tanohatamura Shimohei-gun, Iwate

☎ +81-80-9014-9000

http://laureole7.com/

◎ K.H.Base (Yamada-machi)

9-89-14 Osawa Yamada-machi Shimohei-gun, Iwate

☎ +81-90-7077-3581

http://khbase.com/

Tono:

◎ Koya Yauemon

54-41 Tassobe, Miyamori-machi Tono-shi, Iwate

☎ +81-90-4553-9882

http://www.koya-yauemon.net/

This coverage tour has been implemented under FY2017 “New Tohoku” Interaction Model Project led by Japan’s Reconstruction Agency.

If you are interested in traveling to Tohoku, learn more about our travel plans designed to facilitate the discovery of food culture in farming and fishing villages!!

https://r-tsushin.com/en/journal/japan/food_tourism_tohoku.html